US President Donald Trumpon Wednesday ratcheted up his tariff offensive up to 245% on China. He also declared it’s up to China to return to the negotiating table after Beijing backed out of a high-stakes Boeing aircraft deal.“The ball is in China’s court,” Trump said in a statement delivered by White House press secretary Karoline Leavitt. “China needs to make a deal with us. We don’t have to make a deal with them.”

In reaction, China said it was “not afraid” of engaging in a trade war with the United States, while repeating its call for dialogue. “If the US really wants to resolve the issue through dialogue and negotiation, it should stop exerting extreme pressure, stop threatening and blackmailing, and talk to China on the basis of equality, respect and mutual benefit,” foreign ministry spokesman Lin Jian said.

Why it matters

Despite China’s tough talk, it faces deeper economic vulnerabilities than the US, and a prolonged trade war could inflict lasting damage on its export-reliant economy. While both nations are absorbing shocks, the pain may be far more acute for Beijing — not least because of how much it still depends on American consumers.

“They’ll run out of bullets first,” Trump reportedly told aides during his first administration.

That sentiment is now being stress-tested as China grapples with a triple blow: Plunging exports, sluggish consumer demand, and a weak job market.

Why China is at a disadvantage

Despite its rhetoric, Beijing is boxed in—economically, politically, and strategically. Here’s why:

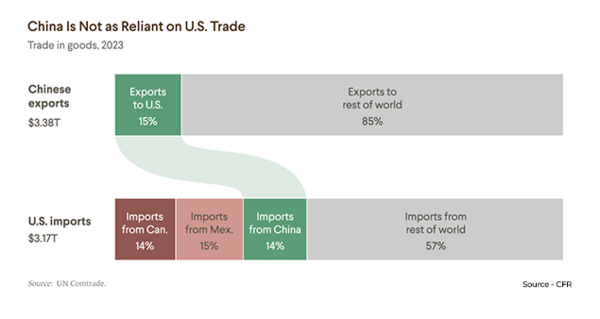

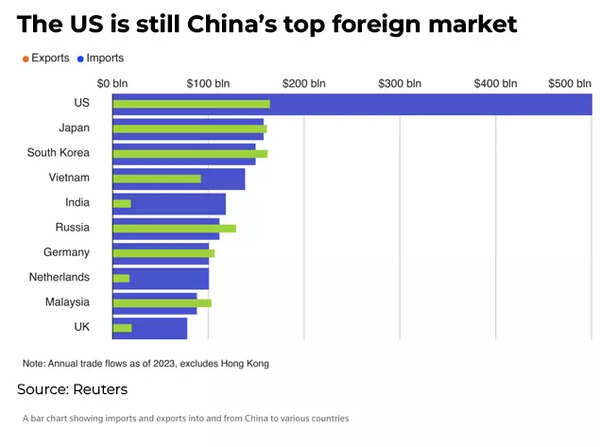

1. Exports still power China’s economy

Despite its attempts to diversify exports, China still remains deeply reliant on US markets. Exports account for nearly a third of its GDP, and up to 20% of that goes to the US when indirect trade routes are factored in. Goldman Sachs estimates that up to 20 million Chinese jobs depend on these exports. Beijing has talked for years about pivoting toward domestic consumption, but the reality is that its economy is still built to sell to the world—especially to America.A sudden collapse in US-bound trade will hit employment, growth, and local government revenue hard.

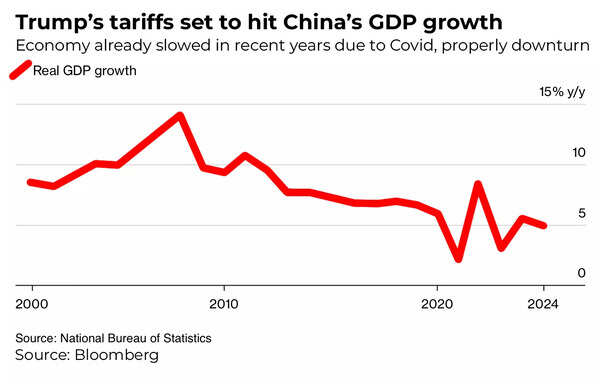

2. China is fighting from a weaker economic position

China’s economy is already under stress—from deflation, a property market crisis, and weak private sector investment. Tariffs only deepen those vulnerabilities. While Q1 growth was 5.4%, much of that came from front-loading shipments to beat the tariff clock. Forecasts are already falling: Nomura cut its 2025 GDP estimate to 4%, UBS to 3.4%. China can’t afford another economic shock, especially one it didn’t initiate.Yet that’s exactly what this trade war is becoming. As per estimates, China’s GDP growth may get a hit of about 2% if the trade war continues.

3. The domestic market can’t absorb the shock

Officials tout China’s 1.4 billion consumers as a buffer against trade shocks. But household confidence is fragile. Property prices are falling, youth unemployment is high, and consumer sentiment has yet to rebound post-Covid. People are saving, not spending. Many middle-class households already saw their wealth eroded through the real estate slump, and stimulus has only provided short-term relief. Domestic demand is not yet strong or stable enough to replace the loss of US market access.

4. The Communist Party’s legitimacy is at stake

Unlike Washington, where economic pain can be chalked up to politics, China’s ruling party has no opposition to blame. The social contract in China hinges on stability and rising living standards. A prolonged trade war that drives unemployment up and incomes down could create unrest—and that’s politically dangerous for the leadership. Beijing may talk tough, but it knows that economic discontent can turn volatile fast, especially in urban centers where jobs are drying up.

5. Beijing lacks the agility of Trump’s trade policy

Ironically, Trump’s trade war is easier to escalate than Beijing’s. The US president can impose tariffs almost unilaterally- even with a post on X. In contrast, China’s policymaking is bureaucratic and consensus-driven, even under Xi Jinping. It takes time to analyze, agree on, and implement countermeasures. That makes China slower to react and easier to corner. In trade diplomacy, speed and unpredictability are assets—and Trump has both.

Between the lines: China’s retaliatory tools aren’t just limited – they’re risky

- Rare earths leverage? Most US buyers get them in component form, and export bans would only accelerate alternative supply chains in places like Australia and Canada.

- Devaluing the yuan? It could backfire by triggering capital flight and domestic inflation — already a risk in China’s consumer-sensitive economy.

- Selling US Treasuries? That would raise US interest rates but also strengthen the yuan, making Chinese exports less competitive – the opposite of what Beijing wants.

- Corporate pressure campaigns? Beijing has begun cracking down on some US firms through antitrust probes and film bans. But too much pressure could scare off foreign investors, worsening China’s post-pandemic investment drought.

What they’re saying

From the White House, the message is clear: Trump sees no need to compromise. Press secretary Leavitt repeated the president’s view that China “reneged” on a Boeing deal and failed to honor commitments under a previous trade agreement.

“There’s no difference between China and any other country except they are much larger,” Leavitt said.

Beijing disagrees — but behind its confident posture lies real concern. Chinese officials admit the new tariffs could “put certain pressures on our country’s foreign trade and economy,” said Sheng Laiyun of the National Bureau of Statistics.

That pressure is already visible on factory floors.

At the Canton Fair, a sprawling trade exhibition in Guangzhou, Chinese vendors shared frustration and fear. “This is so hard for us,” said Lionel Xu, whose mosquito repellent kits once filled US shelves. Now, they sit in a warehouse.

“We are worried. What if Trump doesn’t change his mind? That will be a dangerous thing for our factory,” Xu told BBC.

Zoom in

China’s messaging – both at home and abroad – is shifting between bravado and damage control.

State media has leaned into national pride, urging people to “eat bitterness” and endure hardship. But that’s easier said than done in 2025, when more than half the Chinese population is now overweight, and urban living expectations have surged.

The average Chinese consumer – especially the emerging middle class – isn’t eager to go backward. Add to that an already battered property sector and a soft job market, and the public appetite for pain may be limited.

Even official optimism is hedged. China’s customs authority recently insisted that “the sky won’t fall,” but also highlighted the need to boost domestic consumption to offset losses from declining US trade.

The looming question: which side may blink first

For now, both Trump and Xi Jinping are locked in a high-stakes faceoff. Trump’s rhetoric suggests he’s betting on economic attrition – expecting US voters to tolerate short-term inflation more easily than China can withstand a hit to its growth model.

Still, the risk of political backlash at home is real. Soaring prices on Chinese-made goods – from umbrellas to electronics – could pinch American consumers. Democrats are already labeling Trump’s tariff strategy a “Trump sales tax” on working families.

But China is more poorly positioned for a drawn-out trade war. Its economic vulnerabilities — from weak household demand to export dependence — are more severe than those in the US. Trump, unpredictable as ever, may yet reverse course. But unless he does, Beijing’s best option may not be escalation — it may be patience.

(With inputs from agencies)